January 2020

On January 10, 2020, the first SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence was posted on an open internet depository by Chinese researchers, confirming that the pneumonia-like outbreak in Wuhan, China—reportedly occurring since November 2019—stemmed from a coronavirus. The Chinese government denied the virus was spreading among humans until January 19.

On January 21st, a Washington state resident who had recently traveled to Wuhan became the first person in the United States with a confirmed case of the novel coronavirus.

Two days later, the Chinese government locked down Wuhan, a major transportation hub and city with a metropolitan population of 11 million people.

On January 31st, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, was identified in Santa Clara County. It was a man who had recently traveled to Wuhan. That same day, the World Health Organization (WHO), for only the sixth time in its seventy-three-year existence, declared a public health emergency once the worldwide death toll from SARS-CoV-2 passed 200 and after an exponential jump to more than 9,800 cases.

February 2020

A few days later, the second confirmed COVID-19 case—unrelated to the first one—was identified in Santa Clara County. She had also just returned home from Wuhan.

On February 6, 2020, 57-year-old Patricia Dowd—a resident of San Jose, CA—was the first known death caused by COVID-19 in the United States. She had no foreign travel history.

At the time, I worked at a community health clinic in Fremont, a sprawling suburb bordering Santa Clara County. A standing sign at the clinic’s main entrance posted information about the novel coronavirus. It warned patients about the virus and noted that all patients would be screened for any recent travel to China, or contact with anyone who had recently returned from China.

A few memorandums began to circulate at work. The guidance provided to us by clinic management was in adherence with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines in preventing the spread of germs:

- wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol if soap and water are unavailable,

- avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands,

- avoid close contact with sick people,

- stay home when you feel ill,

- cover your mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing, then wash your hands after safely disposing of the tissue,

- clean and disinfect frequently

touched objects and surfaces.

Memes making light of the novel coronavirus were circulating throughout the interwebs (much like the virus itself):

On February 26th, the first COVID-19 case of unknown origin in the United States was confirmed from a Solano County resident, a county just north of the Bay Area. Back then, all COVID-19 testing was conducted solely through the CDC. They initially refused to test the person since they had no known exposure to the virus via travel or close contact with a known infected individual. Eventually, they caved and tested the individual and then revised—broadened, basically—their testing criteria.

The term “community spread,” which the CDC defines as the spread of an illness for which the source of infection is unknown, became commonly known.

With the first U.S. case of COVID-19 via community spread, the invisible virus became like a mysterious boogieman lurking out there. This is when fear began to set in for me.

Then, on February 27th, President Donald Trump had

this to say about SARS-CoV-2: “It’s

going to disappear. One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.”

March 2020

My wife and I continued to commute from Hayward to Fremont with our two-year-old son via BART, the Bay Area’s light rail transit system. Our train ride was typically fifteen minutes in duration. It was a reverse commute so our morning train was never crowded, unlike the ones rumbling north into downtown Oakland or San Francisco.

With the specter of COVID-19 descending upon our region, the three adjustments we made to our commute was to ① keep our son strapped in his stroller so he wouldn’t sit or crawl on the train seats, ② keep ourselves from touching any surfaces as much as possible, and ③ sanitize our hands immediately after exiting the station.

Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 Contagion, a film that attempted to realistically depict a global pandemic, was trending on streaming platforms.

Over the first three months of 2020, Netflix added nearly 16 million new subscribers.

On March 9th, Santa Clara County announced its first death from COVID-19.

That week, Maria and I saw a noticeable decline in BART ridership. But we continued to ride even though we were beginning to feel like it was risky to ride public transportation.

Two of my colleagues, including my manager, told me their morning commutes were all of a sudden significantly shorter with less traffic on the highways. A typical hour-long commute dwindled to a manageable twenty-minute drive.

On March 10th, University of California, San Francisco, one of the most renowned medical facilities in the nation, convened a panel of experts to discuss COVID-19. According to an internist who attended the panel, experts predicted that between 40 and 70% of Americans could become infected within the next 18 months. Assuming a 1% mortality rate from the novel coronavirus, and 50% of the U.S. population becoming infected, they predicted 1.5 million Americans could die if no effective drug or treatment regimen was found.

At work, I began to wash or sanitize my hands whenever I touched any communal surface, like the bathroom door handle, or a handle from the break room faucet.

And then, one day, a colleague from the Finance department didn’t come into work. She ended up missing a few days. Soon after, it was rumored that she was in quarantine after her husband, who works at an airport, may have been exposed to someone infected with the virus.

I began to use the bottom of my shoe to flush the toilet in the employee restroom. I was paranoid about handling any common surface, like the sliding lock on stall doors.

I began to use one or two fingers to open and close doors. I also began to use my foot to open the swinging bathroom door at the clinic office.

In short time, my knuckles became raw from excessive handwashing and sanitizing.

At work—the only public indoor space I frequented then—my objective was to decrease the usage of my hands to navigate the office. It became a game—what new inventive ways could I devise to not use my bare hands.

On Wednesday, March 11, 2020, everything went to hell: the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic and Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert tested positive for COVID-19 and the National Basketball Association—the premier basketball league on Planet Earth—suspended its season. For many of us in this country, this was when shit got real.

The rest of that week, my manager and I continued to come into the office, just like everyone else at our clinic. But then we learned members of our IT staff were beginning to work from home.

I began to avoid our break room altogether. I ate lunch at my desk or I would dine out by myself at infrequently visited nearby cafes and restaurants.

On March 13, 2020—though it wasn’t widely reported then— 26-year-old Breonna Taylor was murdered in her apartment by Louisville police in search of signs of drug trafficking while investigating her ex-boyfriend, Jamarcus Glover.

I began to obsessively read about anything related to the pandemic. I combed through the New York Times using my app. I read Vox and The Atlantic’s coverage of the pandemic.

At home, I was a building cloud of fear and worry.

One day, my manager and I had a regular half-hour check-in. She was also keeping up on the news about the pandemic. We were both wary about meeting in her small office, even if we kept six feet from one another. Instead, I stepped into an unoccupied office next to her office where we both spoke over the phone for our check-in.

We were both concerned about our organization’s seemingly nonchalant response to this looming health crisis.

She told me one of the clinic’s senior management leaders shamed her when she expressed apprehension in having an hour-long meeting inside a small conference room with six to seven other staff members.

The signage at the main entrance to our clinic changed. As the coronavirus began to spread throughout Europe, the sign noted that COVID-19 screening would no longer be limited to people who had recently traveled to and from China, or come into contact with anyone from China.

A few days before my son’s third birthday, I watched renowned epidemiologist, Michael Osterholm, on The Joe Rogan Experience. I remember Dr. Osterholm basically told Rogan that the virus could infect people via airborne transmission, and he also noted that the CDC guidelines were mostly useless in preventing the spread of this virus.

My anxiety spiked. And my wife and I had been planning a birthday party for our son.

The day before the birthday party, I snapped. I wanted to cancel the party. Our parents were coming. What if someone infected with the virus came to the party and got our parents sick and what if they ended up dying from it? How could I ever live with myself afterwards?

Despite my apprehension, we forged ahead and held the party at our small two-bedroom house. This is the text message I sent to our guests the day before:

Hi everyone,

This is our COVID-19 update concerning Miguelito’s party tomorrow. This morning, Maria and I have strongly considered cancelling the party but we think we can go ahead with it with these precautions:

1. For everyone’s safety, we’re going to discourage hand shaking, hugging, and kissing on the cheeks.

2. We’re going to ask everyone to wash or sanitize their hands when they first come in, please. We’ll have hand sanitizers throughout the house. Feel free to bring yours.

3. We’re sanitizing the crap out of our house today and tomorrow.

4. Food will be served by 1-2 folks, not buffet style. We already have volunteers for this.

5. Even if it rains, we’ll try to have everyone relatively spread out in and around the house. At most, we’re expecting about 20 people, which includes everyone (i.e. the kids, Maria and me).

6. If you’re feeling ANY symptoms of illness, please do not come.

7. All this said, if you feel uncomfortable and decide not to come, we are totally, totally understanding.

All these precautions are really meant to protect our most vulnerable family members. That’s what this is about. This virus is out there and experts in virology and epidemiology believe it is already to [sic] late to contain this virus in our country.

Thank you very much for hearing me out. If you have any questions or concerns, please call or text me.

Love,

Juan(ito)

Most of our guests came. My then-eighty-one-year-old father was the only one who stayed home.

In the end, thankfully, no one got infected from attending our party. In retrospect, we shouldn’t have held it. That’s a no-brainer.

As the party was happening, with dark rain clouds up above, it felt like many of us knew it might be the last time we would have such a gathering for some time.

And then, on Monday, March 16, 2020, six of the regional public health departments jointly declared a shelter-in-place order. The first such directive in the United States in response to this pandemic.

On that day, my wife and I drove to Fremont with our son for our morning commute.

Later that day, my department received unexpected good news: management was going to allow us to work remotely from home.

Paperwork was haphazardly signed. Soft files from our shared drive were hastily copied to a personal thumb drive. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, my then-employer had no telecommuting policies.

There were no work-provided laptops available for me to take home, but I didn’t care. I had a personal laptop. I would find a way to make it work.

I felt like we were getting bailed. Spared.

But I felt awful, AWFUL, and guilt-ridden that other administrative coworkers—like my open office neighbors, the ladies from the Billing department—weren’t permitted to work from home.

Our collective sense of time was warped.

Everyday life was abundantly focused on the present.

During those first few weeks of pandemic lockdown, I had some exceptionally intense and vivid dreams. I couldn’t recall them later that day, but their weightiness sat with me after I arose—and I know I wasn’t the only person experiencing this uptick in vivid dreams.

According to a National Geographic article about what they called “pandemic dreams,” they were “colored by stress, isolation, and changes in sleep patterns—a swirl of negative emotions that set them apart from typical dreaming.” I personally believed it was evidence of Jung’s collective unconscious, which is “a universal version of the personal unconscious, holding mental patterns, or memory traces, which are shared with other members of human species.”

Before the pandemic, I typically went out each week to buy groceries with my son.

At the time, due to a fear of shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for our healthcare workers, the CDC advised the public to not purchase PPE, such as surgical masks or N95 respirator masks if we weren’t sick. But, my family had unused N95 masks from dealing with last year’s wild fires.

After I started a thread on Facebook with trusted friends, I concluded that people should ideally be wearing facial masks in public to prevent the spread of this highly-infectious virus.

Our venerable public health institutions didn’t provide this crucial guidance. And in retrospect, this would be emblematic of what would come in the United States.

During those first weeks of the pandemic, my trips to the grocery store became a source of great anxiety. All of a sudden, mundane trips to the supermarket took on a life or death feel.

I would nervously cough while I got dressed and ready to go to Safeway.

On that first trip to the supermarket after the shelter-in-place order was set, I wore an N95 mask and disposable gloves. After I slipped on the gloves, I used a Clorox disinfecting wipe to clean the shopping cart’s handlebar and shopping cart seat.

Prior to the pandemic, if I went alone to the store to buy our groceries, I often listened to podcasts or music through headphones to drown out the god-awful music that often played at the supermarket. But when the pandemic first hit us, I left the headphones home. I figured I should have all my senses at full disposal. If I heard anyone sneeze or cough in a nearby aisle, I should be attentive and avoid them.

The rumors were true: people were hoarding toilet paper, bottled water, and sanitizing supplies.

I was aghast when I first saw an entire aisle with shelves cleared of toilet paper. Some frozen goods were getting wiped out too.

In terms of natural disasters, the San Francisco Bay Area is earthquake country. It’s not an active war zone, nor a hurricane region, so I had never seen anything like this in my entire life.

When I finished buying my groceries, I tossed the damp, oftentimes torn disposable gloves in the trash, then loaded my grocery bags in the car. After I carefully took off my mask using the earloops, making sure to not touch the mask itself, I used hand sanitizer to clean my hands.

Once I came home, I drove up our long driveway. I entered through the back door. I would take off my shoes before entering the house, put my used N95 mask on top of our dryer, which was high enough to be past our son’s reach. Like a good boy, I’d wash my hands with hand soap and water for twenty seconds before I would put our food items away.

To avoid weekend crowds, one Monday morning, I woke early to go to our nearby Costco Business branch when they first opened at 7 a.m. I arrived at 7:03 a.m., and there was a long, U-shaped line of shoppers formed in the parking lot to enter the store.

Costco was limiting the number of shoppers who entered their warehouse.

One employee was assigned to sanitize handlebars on shopping carts in the parking lot. I waited half an hour to get to the entrance.

They had a large dry erase board at the front of the store that noted what items were currently out of stock. The list included toilet paper, paper towel rolls, sanitizing wipes, and hand sanitizers.

In our region, Costco was one of the first stores that required customers to wear face masks. I also remember they were the first store I shopped at that allowed (or encouraged) their employees to wear face masks.

Management from grocery chains like Trader Joe’s and Safeway were initially reluctant to allow their employees to wear PPE. Their excuse, or corporate logic—whichever one you wish to call it—was that they didn’t want their customers to feel alarmed when shopping at their stores.

Costco was also the first major retailer in our area to adjust their checkout line setup and procedure: they put stickers on the floor to space customers six feet apart and asked customers not to handle and place items for purchase on the checkout conveyor belt. They also erected plexiglass sneeze guards to protect their checkers.

In the coming weeks, Safeway and other supermarkets followed suit by mounting plexiglass sneeze guards at their register area.

Meanwhile, in Western Europe, the novel coronavirus was ravaging Spain and the Lombardy region in Italy.

On March 21, 2020, it was reported that 793 people had died in one day from COVID-19 in Italy. At the time, it was a devastating and frightening total to fathom.

In the United States, it was widely reported that hospital beds and ventilators in the Lombardy region were at full capacity and their hospital staff were oftentimes forced to decide who got to live—who would have access to a ventilator. Many of us feared that this is what we would soon face in the United States.

Words and terms that entered our daily vernacular included: “essential worker,” “PPE,” “asymptomatic,” and “flattening the curve.”

In the news, it was reported that the virus could survive on hard surfaces, such as plastic and stainless steel for up to 72 hours and cardboard for up to 24 hours. This scared the shit out of me.

Naturally, if the virus could live on surfaces for days or hours on end, people (like me) began to worry about how we should handle groceries brought home.

I read two online articles that recommended washing your produce. At the time, when the virus was new and we collectively weren’t familiar with it, this guidance seemed sensible. From picking the fruit and vegetables to transporting them to a warehouse to distributing them to stores, how many people handled the produce we purchase? If one of those people was infected and didn’t practice sound hygiene, the virus could be on the produce.

After I’d shop at the supermarket, I began to come into our house through the back gate and back door. I would remove my shoes and leave them outside, then step in and carefully set my used N95 mask in a paper bag on our dryer to rotate with another used N95 mask. (Before I implemented this practice, I tried to disinfect a used N95 mask one time by sticking it into the oven at a low temperature. I followed the guidelines I had read in an online article and ended up scorching the mask so I didn’t try that again.) I didn’t do it all the time, but sometimes I would take off my shirt and immediately toss it into the laundry basket.

On at least two occasions, I lightly washed our produce—like apples, oranges, and bananas—with a minute solution of dish soap and water as recommended in one of the articles I read. I would leave the dry goods in a shopping bag for at least a day before I would tuck them away in our cupboards.

What really scared the shit out of me was the first-hand stories I would read online of people who masked up and washed their hands and swore they took precautions when out in public and still caught the virus.

During the first shelter-in-place order, I rode my bike into our downtown area. I had bought a cloth mask, which I had tucked into my pocket. A block from our house, I turned a corner and saw a destitute woman sitting on the pavement against a church. She coughed as I passed by along the sidewalk. I was at least six feet from her, but I was scared if it was possible to catch the virus if she had been infected and if I had cycled directly into the area where she had coughed.

By the fourth week of March 2020, BART ridership had plunged 92%.

BART’s Board Vice President tweeted: “BART estimates fare & tax impacts of coronavirus could lead to between $286-442 mil revenue loss this fiscal year.”

In Murcia, Spain, a man left his house wearing a Tyrannosaurus Rex costume, broke their COVID-19 lockdown orders and subsequently encountered local police.

In Spain, in cities like Barcelona and Madrid, multiple video recordings of musicians—seasoned musicians and half-assed ones—singing and playing from their balconies during lockdowns were going viral.

Late Sunday morning on the first weekend under shelter-in-place orders, my family and I drove south on Highway 880 to hike at one of our regional parks. At one point, I saw a handful of cars in front or behind us. The nearest cars were about a quarter of a mile away. I have grown up in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1986, and my wife has also lived here most of her life, and we had never seen that heavily-trafficked highway so sparsely traveled during daylight.

With the right timing, a

person could have safely strolled across all four lanes.

|

| March 22, 2020 |

It was eerie and startling to see the highway so barren. It reminded me of Octavia Butler’s 1993 dystopian sci-fi novel, Parable of the Sower, where California’s highways turned into dangerous throughways for people to traverse.

On March 24th, Trump went on Fox and said he "would love to have the country opened up and just raring to go by Easter."

Out on the East Coast, New York City—a global tourist destination and a major transportation hub—was brutally hit by the pandemic.

Newspapers reported PPE shortages at our nation’s hospitals.

At Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, some nurses were using Hefty-brand garbage bags as stand-ins for protective medical gowns that were in short supply.

Early in the pandemic, directions and instructive videos on how to properly remove surgical masks were circulating through social media. The critical step was not grabbing the front of the mask, but pulling it off from the earloops. It was a big deal then, I suppose, for people like myself who wanted to make sure it was being worn and removed correctly. But, then practically everywhere you went, you would inevitably run into people who wore masks over their mouths but didn’t cover their noses, or the ever-popular “chin mask”:

I read articles about doctors and nurses who would come home after their hospital shifts and take off every garment either before or immediately after stepping into their home, and then shower. As much as they wanted to, they couldn’t hug their own children for fear of infecting them.

On March 27, 2020, the U.S. reached the most COVID-19 cases in the world.

On March 31st, New York City alone surpassed 1,000 total COVID-19-related deaths. The dead were piling up in hospitals in Brooklyn and Queens, which were especially hard hit.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) sent refrigerated trucks to New York City to serve as makeshift morgues.

I watched a viral recording of a Facebook live video from John Lee, a Brooklyn, NY resident as he filmed a forklift raise a dead body into a makeshift morgue parked outside a hospital. “This is for real, this is Brooklyn, y’all,” Lee said. “This is for real, y’all,” he repeatedly said, and his quivering, tearful voice and shaky phone camera was seared into my memory, where it will probably always remain.

Mr. Lee’s comment on his Facebook live video reads: “PLEASE!!! WAKE UP BEFORE YOU DIE!!” 36 liked his comment, 15 loved it, 5 people laughed at it, and 2 users responded with Facebook’s sad emoji.

My friend, Justin, lived in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood. He lived four blocks from a hospital. He told me he heard an ambulance siren all day and all night through April and May.

April 2020

In The Atlantic’s May 2021 issue, writer Melissa Fay Greene penned an article focused on what we will remember about the pandemic. She wrote: “Though we may vividly recall ‘how it began,’ many of our pandemic memories will be hazier.”

On one of my grocery store runs, I saw a kid sitting in a grocery cart, donning a surgical mask. It broke my fucking heart.

Novelist Arundhati Roy wrote an article about the pandemic in The Financial Times that was widely circulated. She wrote:

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”

Writer Rebecca Solnit was interviewed by Vox. They asked her to imagine life after this pandemic. She said, “And so you’ll always have the winners of the old system pushing hard to reassemble it after it’s shattered in front of our eyes. But the status quo is dead. And the rest of us are saying, ‘Let’s go forward. Let’s not go back. Let’s go another way.’”

Here’s another noteworthy snippet from her interview: "Going forward, a lot of what happens in terms of transforming societies depends on transforming governmental systems and that depends on how we tell the story of what happened."

Despite all the fear and dread produced by the pandemic, I felt a fleeting sense of excitement—that thoughtfulness and inventiveness would be needed to survive, to make the best of this challenge to our species.

I was so naïve to believe that in the aftermath of this pandemic our nation would change for the better.

During that time, I saw a video from Taiwan of an infrared temperature scanner installed at the toll gate of one of their metro stations. They also had a young station attendant standing at the toll gate kindly asking passengers to adjust their face masks to cover their mouth and nose. It was clear to me then that this level of proactive health measures and compliance from their public would be crucial in controlling this pandemic.

Early on, I feared America’s rugged individualist ideals would have a detrimental impact on our nation’s pandemic response.

In short time, the usage of facial coverings gradually and noticeably increased. About three weeks after the shelter-in-place order was placed, I noticed that at least half of the customers at our local Safeway were using face masks.

On April 3rd, the CDC recommended that people wear cloth or fabricface coverings when entering public spaces.

On April 10th, New York recorded more COVID-19 cases than any other country besides the United States.

Iowa’s meatpacking plants experienced a number of COVID-19 outbreaks. Hundreds of Tyson employees at their Waterloo pork processing plant refused to work, alleging their employer was covering up the presence of COVID-19 and allowing sick people to keep working. Governor Kim Reynolds, a Republican, did not intend to force Tyson to shut down its plant. Ultimately, more than 180 workers from that plant tested positive for COVID-19.

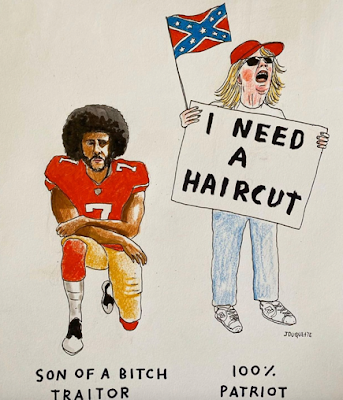

Across America, this great country founded on genocide and slavery, it didn’t take long for flag-waving, freedom-loving Americans to complain about barbershops and hair salons being shut down because they wanted to get their hair trimmed.

While many supermarkets and retail stores were perpetually wiped out of toilet paper, paper towels, disinfecting products, and water, our nation’s truck drivers, grocery store employees, and farmworkers were rightly elevated to the status of essential workers.

Meanwhile, remote workers and schools across the country quickly pivoted to the video teleconferencing software program, Zoom, to facilitate business meetings and virtual instruction. The New York Times reported that global downloads of the Zoom, Houseparty, and Skype apps increased more than 100 percent in April 2020.

In a startlingly short amount of time, “Zoom fatigue” became a phenomenon and thusly entered the public lexicon.

Playgrounds were closed. At our nearest playground, swings were tied around the support bar to prevent people from using them.

Rims from communal basketball courts were also removed.

It felt like this virus was taking all the joy from our lives.

On April 23, 2020, President Trump held a White House press briefing in which he suggested that shining white light directly into the body and injecting disinfectant could treat coronavirus. If any American of sound mind had any lingering doubt about his aptitude to lead our federal pandemic response, this was the precise moment we unequivocally knew we were absolutely shittastically fucking screwed.

As my family and I primarily shuttered indoors, I began to listen to podcasts devoted to the COVID-19 pandemic, like The Atlantic’s Social Distance and the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy’s (CIDRAP) The Osterholm Update, which I zealously listened to every week.

I listened to a Radio Ambulante podcast episode about a family in Madrid where half of the household got sick with the virus while the family members living in the other wing of the house tried to take care of them and not get infected. I studiously listened to it, dreading that the learnings I gleaned from it would someday help me and my family.

On April 29th, the Pentagon officially released videos of "unidentified aerial phenomena."

May 2020

My wife and I remotely worked from her parents’ house in Fremont while they graciously took care of our son. My mom’s best friend happens to live next door, so we occasionally saw my mother in passing during the week. One time, my wife saw my mom drive her friend in her car along with another elderly woman and none of them wore masks, and they didn’t roll down the car windows.

In early May, 2020 struck again: Asian giant hornets (a.k.a. “murder hornets”) were spotted in the United States for the first time.

People on Twitter and social media blew up: first UFOs in April 2020, then murder hornets in May. What the fuck are we getting in June?

On May 8th, a network of 3,000 churches in California announced that they planned to defy Governor Gavin Newsom’s state health orders and reopen in-person services in the coming weeks. In true American fashion, the announcement was made in front of the Water of Life Community Church, a megachurch in Fontana, CA with a 3,300-seat auditorium that cost about $20 million to build.

I continued to obsessively read newspaper articles from the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times in which infectious disease experts weighed in on the risk of social activities. In earnest, it seemed like better guidance than what the CDC was providing.

In mid-May, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds announced that she was planning to reopen their economy and end Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation payments that all of the state’s unemployed workers were originally scheduled to receive until September 2020. Reynolds was joined by Republican governors in Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, South Carolina and Tennessee in ending the federal programs.

Early on in the pandemic, this was a telltale sign that the continued production of capital was far more important to our political leaders than the health and safety of its citizens.

COVID-19 survivors were oftentimes ostracized by friends and family who were afraid of catching the novel coronavirus from them.

On May 12th, a little more than three months after the first U.S. death from coronavirus, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 passed 80,000.

As if real life wasn’t perilous enough, the media began to warn its citizenry that hand sanitizers in cars could explode from high heat or direct sunlight.

If you ask me, the highlight of the pandemic occurred on May 15, 2020 when pictures of Father Timothy Pelc using a squirt gun loaded with holy water to provide drive-thru blessings at St. Ambrose Parish in Detroit went viral on social media.

Throughout the month of May, my older sister—who lives in San Francisco—frequently posted on Facebook pictures of herself socializing with other people without keeping a physical distance. I saw a selfie of her riding in the back of a rideshare car with her middle-aged husband and fellow party-going friend. They wore cloth masks in the car, but my sister—who graduated from a respected private Jesuit university—somehow or another thought this constituted “being safe.”

Between my partying middle-aged sister and my sixty-five-year-old mother who seems to think—like many other Latines—que nada va pasar (that nothing bad will happen to her), I became filled with dread that one of them would inevitably catch the virus and die.

Erin Bromage, a comparative immunologist and professor of biology from the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth wrote an informative blog post about the risks of contracting COVID-19 that got millions of views.

On May 22nd, CDC guidelines were updated to reflect that the novel coronavirus primarily spreads from person to person instead of fomite transmission (when a virus is passed via contaminated surfaces).

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd—a forty-six-year-old Black man—was murdered by Derek Chauvin and three other Minneapolis Police Department officers for allegedly using a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill at a convenience store. Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier’s cell phone video of Floyd’s murder was widely shared on social media the following day.

Protests of George Floyd’s murder erupted across the United States.

On May 28th, Minneapolis’s 3rd Precinct police station was torched in the George Floyd uprising. Not coincidentally, the next day, Derek Chauvin was arrested and charged in George Floyd’s murder.

My parents held a barbecue on Memorial Day weekend. I had read Erin Bromage’s “How to Have a Safer Pandemic Memorial Day” article and I had no confidence that my mom would adhere to any tips to make such gatherings safer. But more importantly, my older sister was supposed to attend the barbecue and my wife and I thought it was best to avoid her.

Man’s best friend indeed!: a pilot study at the University of Helsinki showed that dogs trained as medical diagnostic assistants couldrecognize the previously unknown odor signature of the COVID-19 disease after only a few weeks of training. The dogs were “able to accurately distinguish urine samples from COVID-19 patients from urine samples of healthy individuals.”

On May 28th, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 surpassed 100,000.

No comments:

Post a Comment